Introduction

In our work on the Vanguard projects in reducing hospital admissions to care homes we have been considering the role of technology within the care homes setting. Areas that we have been looking at include but are not limited to telehealth, I Pad, and more modern, possibly contentious technologies, such as virtual reality headsets.

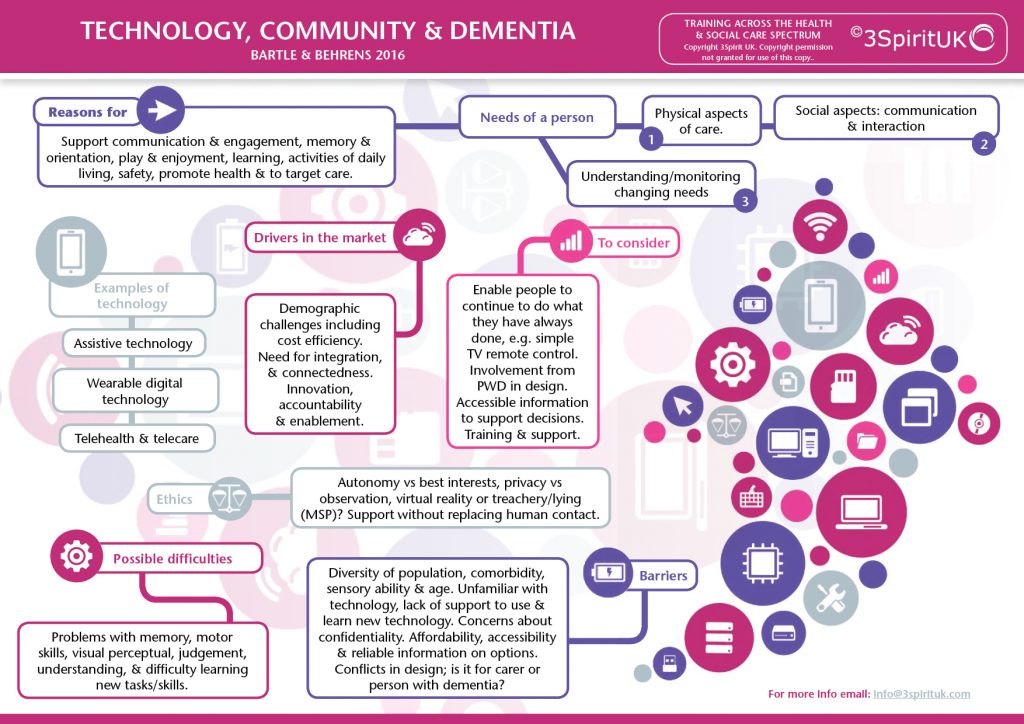

When planning this programme we considered:

How might technology increase social engagement in the care homes, without replacing human contact?

How might technology be used to proactively monitor health, to prevent/detect delirium and / or reduce unnecessary hospital admission?

How might technology be used to promote physical exercise in care homes?

The picture in other areas may well be different, but for here, and for now, at least we seem to be lagging as we found a fairly limited take up. This is also representative of the many care homes that we train. However, the potential use of technology in dementia care has been gathering pace, as new technologies emerge onto the market. A recent coping review that was carried out by GIbson et al (2016) identified 171 product types and 331 services. However, many of these are unregulated, and have not been rigorously tested in research conditions. Despite this there is a significant pull for these technologies. One of the driving factors (although not the only factor) is how these technologies increase efficiencies.

Some definitions:

Assistive Technologies: ‘any device or system that allows an individual to perform a task that they would otherwise be unable to do, or increases the ease and safety with which the task can be performed’ (Royal Commission on Long Term Care, 1999)

Telecare: remote social care monitoring

Telehealth: Telehealth is the remote exchange of data between a person at home and their clinician(s) to assist in diagnosis and monitoring typically used to support people with Long Term Conditions. It comprises of fixed or mobile home units to measure and monitor temperatures, blood pressure, glucose levels and other vital signs parameters

The reasons to use technology are vast, and extend far beyond safety but might also include:

Increase engagement, support independence through multiple mechanisms (prompting memory, orientation, supporting motor skills etc), facilitate proactive and preventative health monitoring, improve wellbeing through multiple domains (including encouraging exercise) and relieve carers stress. Then there are the organisational benefits which might include better targeting of human resource, support communication across teams, support compliance and safeguarding through effective monitoring and reporting.

AT are used by different people in different ways. GIbson et al (2016) usefully categorised the AT into 3 camps: ones that are used by people with dementia, ones that are used on people with dementia and ones that are used with people with dementia. For each of these there is a different set of ethical questions, and differing drivers in design. Who is making the decisions about the purchase and use of these technologies? For informal carer’s the quest may be driven by questions like, how can this technology reduce the caring stress levels? Where these technologies are being used to unobtrusively reduce risks, such as monitoring technologies. How much of this is creating a false sense of security? (Nygard et al 2005).

The context

There has been significant investment in the community to respond to demographic challenges. Policy has stimulated investment in the Assistive Technologies (AT), with the Technology Strategy Board investing £25 million of matched funding between 2008 and 2011. However, whilst these technologies are more widely available in the community, at a practice level, there continues to be real challenges in the uptake, both in the community as well as in care homes. Yet the conversations continue about the evolving possibilities of technology. The Dementia Congress in Brighton this year, as well as the Alzheimer Europe conference in Denmark, featured presentations on ‘robots’. The conversations that ensued included ethics, as well as how these could be used in cashed strapped times.

Greenhalgh et al (2012) suggest that there are several conversations going on around the use of AT, of which ethics is only one. The ‘ethics’ conversation is mainly driven by the professionals working in the sector. Developers and ‘modernists’ are concerned with the benefits and use of AT in saving time, and creating efficiencies. There is also the ‘political’ conversation stating the economic benefits of the telehealth, and telecare markets and the role of industry in influencing, or managing vested interests. Then finally there is the ‘change management’ conversation which argues that there is a mismatch between the system, and actual work practices, and work needed to be completed to address this. These conversations create tensions in the development and uptake of AT, and there is boundless interconnectedness between these.

Nauha et al (2016) looked at the use of AT for people at home with a memory disorder. In this study they also explored how the use of these technologies can facilitate, and support the work of the care staff, together with how the technology is effective in supporting the person with dementia. An important consideration, if we are to address the concerns of the ‘change management’ conversations we need to be thinking unilaterally about the benefits of AT. This means looking at the benefits not only to the individual but also for the service.

Barriers

So as stakeholders continue to battle it out in different forum, on a practice level there is more concern about where and how do I source these technologies? Are they affordable? Will they work? How can they enable? How do they support carers both formal and informal? And finally, and possibly most importantly, how can they be used ethically?

Assistive technologies (AT) might include low tech, to high tech. These might include clocks and signage to support orientation. Devices which prompt and remind, such as medication dispenses, recorded devices or iPad technologies. Alerts and alarms, communication aids or technologies that support recreation and engagement.

Local authority social care support has traditionally been the largest supplier of AT, most of which are tele care, services like just checking can monitor movements / or lack of movements, and successfully identify issues, hopefully before they develop. In addition to telecare, telehealth is having an increasing role. In Croyden a pilot project was undertaken, which successful reduced the admissions to hospitals

Therefore, on a strategic level technologies are being introduced to enable us to work more effectively, to reduce impact on an overburdened NHS. However, many of these technologies are being introduced much later on post diagnosis, often where there are already significant challenges to an individual’s health and wellbeing. As local authority eligibility increases, often individuals are at crisis point before accessing these services, and along with that accessing information about suitable AT. To compensate for this many individuals are now looking in other places for up to date information on the range, and suitability of technologies. Sometimes unsuccessfully sourcing the right technology at the right price. Whilst there are some great websites, like www.atdementia.org which was set up some years ago, brilliant and comprehensive these ‘of the shelf’ products are being purchased without any proper assessment. As the major risk factor for dementia is age, many individuals are living with co-morbidity, including, but not limited to sensory problems, impact significantly on the application, and use of these technologies. In addition, individuals are often have cognitive challenges: memory problems, impaired judgement and visual perceptual challenges.

Cahill et al (2007) found for the AT to be utilised effectively, informal and care staff need to be available to support, show and encourage individuals to use the products. Therefore, what training is being provided to front line staff, and informal carer, on how to maximise the use of these technologies, and how many staff are reluctant because of unanswered ethical concerns?

Potential barriers to the use of technology:

- Accessing timely and suitable information

- Sourcing technology that works with comorbidity

- Accessing suitable assessment

- connection problems

- stigma associated to use

- costs and relative funding for technology

- as much of the technology needs to be supported by others, training is needed

Another major factor, which is often overlooked and not evident in the research papers I have read is the impact of the cuts on the uptake and use of technologies. On the one hand, you might consider that having technologies in place will create efficiencies, however introducing new technology requires change. As we have seen with the introduction of the Home Spirit Tool home care services are simply too stretched to even entertain the idea of piloting new ways of working.

Ethical barriers

In addition to the potential barriers we have the ethical considerations to make. One of the principle concerns is how can technology be used to address loneliness, but without replacing human contact? How might we manage effectively the tensions between surveillance for safety and privacy. As technology evolves it pushes the boundaries around ethical concerns. For example, we have seen the introduction of Virtual Reality, augmented reality for the individual to simulate experiences. Supporters believe that this can support the recall of memories and positive emotion. However, is this a form of treachery (Malignant Social Psychology – Tom Kitwood)?

Conclusion

Despite these ethical challenges, we will continue to explore the benefits and application of AT in our work both in the development of the Home Spirit Tool www.homespirit.org, and in the development of our training. We aim to give our learners the confidence to explore the ethical dilemmas openly as well as engage the people that they support in these conversations. Particularly, how might AT enable us to positively risk take.

References

Gibson, G., Newton, L., Pritchard, G., Finch, T., Brittain, K. and Robinson, L. (2014) ‘The provision of assistive technology products and services for people with dementia in the United Kingdom’, Dementia, .

Gibson, G., Dickinson, C., Brittain, K. and Robinson, L. (2015) ‘The everyday use of assistive technology by people with dementia and their family carers: A qualitative study’, BMC Geriatrics, 15(1).

Greenhalgh, T., Procter, R., Wherton, J., Sugarhood, P. and Shaw, S. (2012) ‘The organising vision for telehealth and telecare: Discourse analysis’, BMJ Open, 2(4), pp. e001574–e001574.

Hagen I; Cahill S; Begley E; Faulkner JP (2007) ‘It gives me a sense of independence’ – findings from Ireland on the use and usefulness of assistive technology for people with dementia. Technology and Disability 19 (2007) 133–142

Nauha, L., Kera nen, N.S., Kangas, M., Ja msa , T. and Reponen, J. (2016) ‘Assistive technologies at home for people with a memory disorder’, Dementia,

Nygård, L. and Starkhammar, S. (2007) ‘The use of everyday technology by people with dementia living alone: Mapping out the difficulties’, Aging & Mental Health, 11(2), pp. 144–155

Rosenberg, L. and Nygard, L. (2013) ‘Learning and using technology in intertwined processes: A study of people with mild cognitive impairment or Alzheimer’s disease’, Dementia, 13(5), pp. 662–677.

Sugihara, T., Fujinami, T., Phaal, R. and Ikawa, Y. (2013) ‘A technology roadmap of assistive technologies for dementia care in Japan’, Dementia, 14(1), pp. 80–103.

Follow Us

Share Us