Most of the choices that people make in life naturally involve some element of risk. Avoiding risks altogether can limit life opportunities, and impact negatively on quality of life. People want choice and control for themselves and safety for those they care for. This is because risk is a concept that tends to have negative connotations, but people take considered risks all the time and gain many positive benefits.

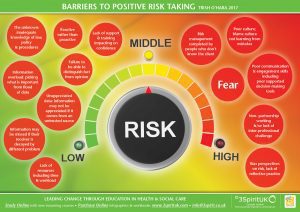

People perceive risk differently, including people who use services, practitioners, and families. This can be difficult for social care practitioners and confusing for individuals and families. Therefore, adopting a balanced approach at a practice level can be a challenge. Balance and proportionality are vital considerations in encouraging responsible decision making.

In our work streams we have been considering:

- What skills do staff need to properly develop positive risk taking in their practice?

- How can learning programmes be developed that inspire and motivate practitioners to take a bold approach to positive risk taking?

- What systems need to be in place to enable a responsive approach to positive risk taking?

Getting out of bed, and all that it entails – getting washed, dressed having breakfast, and taking the bus to work – carries risk. Though, staying in bed could still involve both psychological and physical risks.

Back in the mid 80’s the social care sector often ignored risk assessments. There were risk assessments in place for health and safety of the building and staff. However, what was lacking was person centred risk assessments to support the people using our services to positively live their lives.

I recall us supporting extremely complex individuals to go to Glastonbury music festival. We did this without a risk assessment, and this was back in the day when you could speak to Martin Eavis directly to get free tickets. They were the days of ‘try it and see’.

By the late 80’s risk assessments were firmly and quite rightly in place to ensure staff were confident to support people to try new things, and live as full as life as possible. Managers who would start a sentence ‘Yeah, let’s try that, let’s do a risk assessment’ with a smile. It was as if doing the risk assessment itself was the incentive to make it happen. Over time, I noticed that the sentiment of risk assessment changed. The managers started to say, ‘oh no, you had better risk assess that’. It seemed like the idea that risk assessment had become a way of limiting people. The intention changed. Risk assessment should be used as a tool to support empowerment, and innovation. It should also be used to listen to those that need care and support.

Finding time to embark on meaningful co-production, ensuring the person is an equal partner in the shaping of their services is likely to mean that people will be faced with more choice. Where people are faced with more choice this is likely to lead to options that introduce more risk.

So what is stopping our services effectively undertaking positive risk assessments, what are the barriers?

People perceive risk differently. For instance, it you ask nurses what is the main risk for older people in care homes, they are most likely to say, falls. If you ask social workers, they are likely to be concerned with risks to adequate housing or benefits. If you ask their family, it is likely to be that they are concerned that their loved one is treated badly. If you ask the person themselves, they may be more concerned with losing their identity and/or purpose. We come to the table with a bias based on role and relationship.

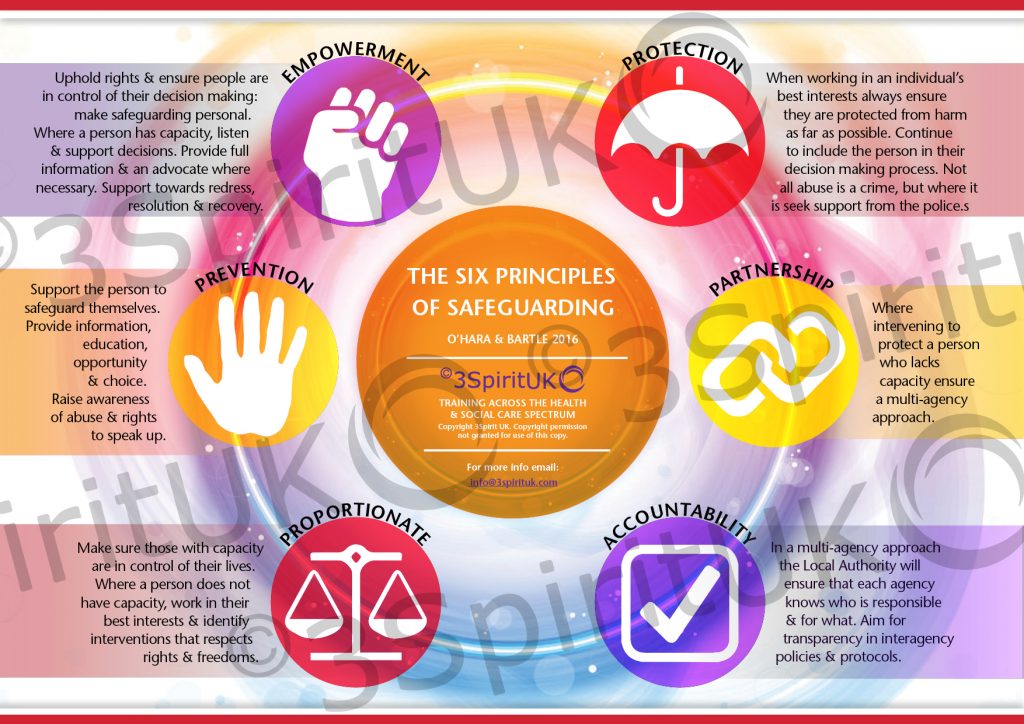

Getting the balance right requires professional competence, partnership working and understanding that safeguarding is about improving quality of life as much as safety, and can only really work if we keep it personal.

Because risk assessment is considered a skilled endeavour, we often see managers or team leaders completing the risk assessment from beginning to end from inside of an office, rather than inside the life of the person. Key-workers need to be trained to understand risk assessment and be part of the process, as they are often the people who know the person best.

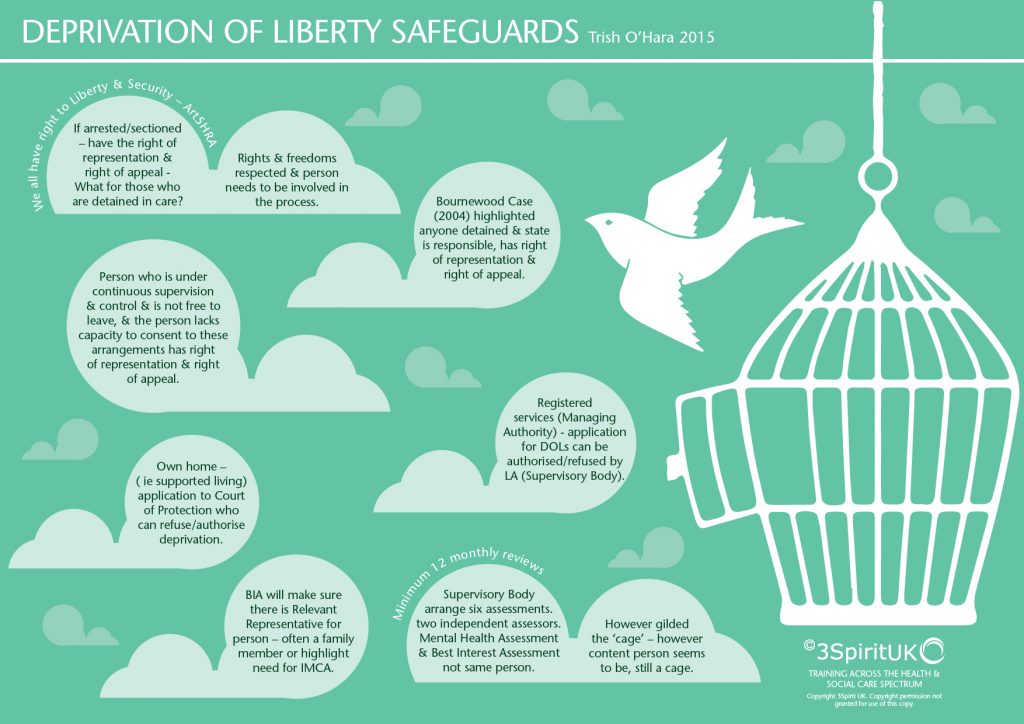

There is also a real fear of being accused of neglect. Staff also struggle to understand that what may be important FOR the person may be in direct conflict with what is important TO them. A disproportionate response that infringes the rights of individuals to make their own, albeit at times, unwise decisions. Often there is a lack of a working knowledge of the Mental Capacity Act and what it means to deprive a person of their liberty. A general lack of knowledge when and where to apply the law.

Ultimately, risk is part of life and arguably the most successful people take many of them. It is impossible to self actualise without taking risks. It’s the only way to face the challenge of Everest. Many of us would make it to the top if we were given the chance to do it at our own pace (maybe years), using our own methods, with the right people and with the adaptations required to help us along the way. We would find our own peak and reflect on our own troughs knowing where we are, where we have been and where we are going.

We will continue to challenge practice in our work streams, and get practitioners to really believe that positive risk taking is a fundamental core of practice.

Trish O’Hara

Follow Us

Share Us