As health and social care trainers we straddle the medical and social model, and believe whole heartedly, holistic, and integrated practice is required to enable positive outcomes, and well-being within our communities. Within each realm of medical and social perspective, many factors which may be viewed in isolation maybe interdependently linked: manipulating one factor, may impact upon others. We need to take a balanced approach, informed by consent, and at times, pharmacological strategies are warranted, and at others times we should consider non-pharmacological approaches.

It is our responsibility, within training sessions, to encourage staff to reflect upon their clients and the complex nature of the conditions, to equip them with skills to observe, report and signpost. One subject raised within sessions is polypharmacy. Many of the services we train are commonly working with comorbidity, and complexities around fluctuating sates, often resulting in competing care and treatment strategies. To support discussions relating to polypharmacy, we developed some resources with the aim to get people to think and reflect more broadly about the topic.

Inappropriate polypharmacy is a very real and present threat, as many prescribing practitioners face tensions between treating common conditions and the risks associated with polypharmacy.

Many people with dementia, together with older population are affected by polypharmacy. Older people generally will have multiple health conditions which require medication. However, given the potential communication difficulties presented with dementia, particularly around problematic pain management, it is possible that there is a higher prevalence of polypharmacy in this group.

There is no clear definition for Polypharmacy: Sometimes numerical: for example greater than 6. Accepting a numerical definition of polypharmacy has the disadvantage: does not recognise that in some cases the combination use of certain medications is beneficial to the older person. Inappropriate polypharmacy is when the person takes more drugs than are clinically indicated.

Polypharmacy is a concern in this group because there are age-related physiological changes that alter the ways in which drugs are handled by the body. This may include:

• Reduced renal function

• Reduced liver function

• Reduced ratio of body fat to water

• Delayed stomach emptying

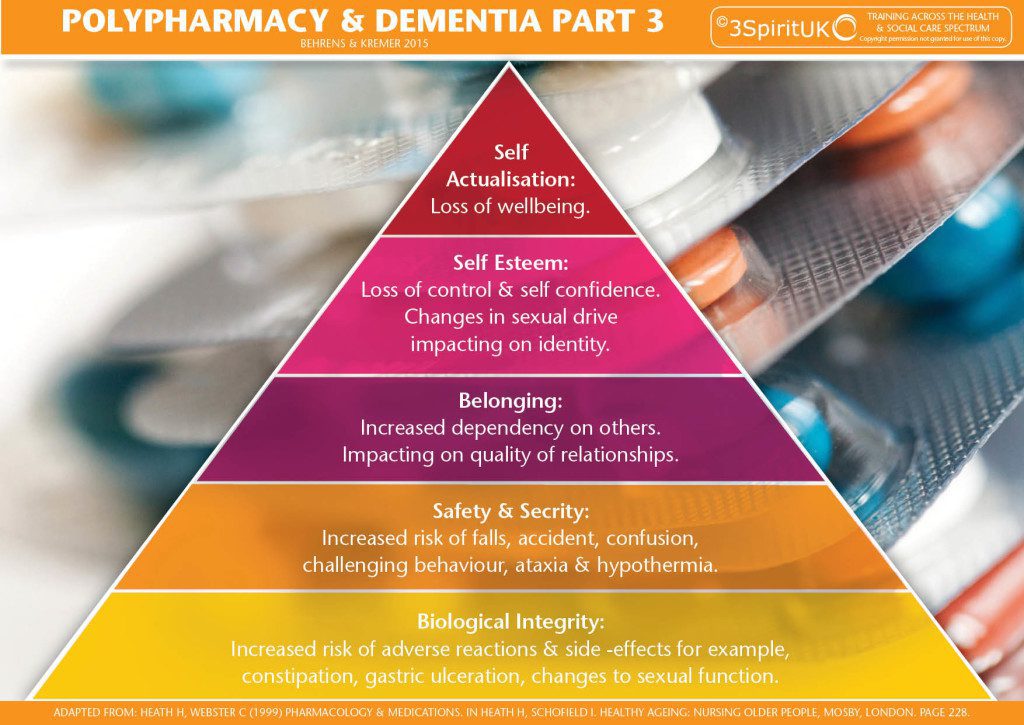

There are substantial risks of polypharmacy: for example, there may be severe side effects, some of which further compound cognitive challenges. There may also be drug-drug interactions and drug-disease interactions. The impact can be far reaching; Side effects may cause drowsiness leading to an increased risk of falls. There may be impacts on appetite and poor nutrition leading to multiple problems, not least a compromised immune system. Further than a physiological level, for example certain medications may impact on changes to sexual drive, impacting on identity and ultimately self-esteem. Changes in mood caused by the medication, coupled with cognitive difficulties may lead to emotional distress and challenging communication. In some instances the inappropriate use of medication can create the very problem that it is trying to solve.

There are many possible causes of inappropriate polypharmacy:

• Multiple physicians

• Self-medicating

• Over the counter medicines including herbal preparations

• Medicine dependent culture

• Medication administration errors

• Treating medication side effects with other medications: e.g. a medication may cause constipation, may then be prescribed a laxative. Alternatively maybe appropriate to consider non drug approach: diet.

When the side effects of medication are misdiagnosed as symptoms of another condition. Further medication is prescribed (Cascade prescribing), further side effects and unanticipated drug interactions may present. Older people with dementia who take a cholinesterase inhibitor and who experience urinary incontinence are more likely to receive an anticholinergic medicine to manage their symptoms

Drugs including some antidepressants, muscle relaxants, antispasmodics, and antihistamines may have anticholinergic effects and, therefore, may cause confusion, blurred vision, dry mouth, light-headedness, constipation, and difficulty with urination and/or loss of bladder control causing additional difficulties for a PWD.

Some examples from research:

In a prospective cohort study of 294 older people 22% percent of patients taking 5 or less medications were found to have impaired cognition as opposed to 33% of patients taking 6-9 medications and 54% in patients taking 10 or more medications.

Also in this paper: Polypharmacy affected patient’s nutritional status. A prospective cohort study found that 50% of those taking 10 or more medications were found to be malnourished or at risk of malnourishment

Jyrkka J, Enlund H, Lavikainen P, et al. Association of polypharmacy with nutritional status, functional ability and cognitive capacity over a three-year period in an elderly population. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2010;20:514–522. [PubMed]

A study in elderly patients with dementia reported that those patients who reported a fall had an increased prevalence of polypharmacy

Lee CY, Chen LK, Lo YK, et al. Urinary incontinence: an under-recognized risk factor for falls among elderly dementia patients. Neurourol Urodyn. 2011;30:1286–90. [PubMed]

American study

Two-thirds of hospitalisations for adverse events involved four medicines or classes — warfarin, insulins, oral antiplatelet agents or oral hypoglycaemic agents — taken alone or in combination

Budnitz DS, Lovegrove MC, Shehab N, et al. Emergency hospitalizations for adverse drug events in older Americans. N Engl J Med 2011;365:2002–12. [PubMed]

References

All Party Parliamentary Group on Dementia (2008) Always a last resort: inquiry into the prescription of antipsychotic drugs to people with dementia living in care homes. Alzheimer’s Society. London.

Kleijer BC, van Marum RJ, Egberts AC, Jansen PA, Knol W, Heerdink ER. (2009). Risk of cerebrovascular events in elderly users of antipsychotics. J Psychopharmacol. Nov;23(8):909-14. Epub 2008 Jul 17.

NHS Information Centre (2012) National Dementia and Antipsychotic Prescribing Audit.

Gill SS, Mamdani M, Naglie G, et al. A prescribing cascade involving cholinesterase inhibitors and anticholinergic drugs. Archives of internal medicine 2005;165:808–13. [PubMed]

http://pathways.nice.org.uk/pathways/dementia

Helen Behrens and Caroline Bartle

Follow UsShare Us