Deprivation of Liberty – Are we spending public monies wisely? Trish O’Hara April 2015

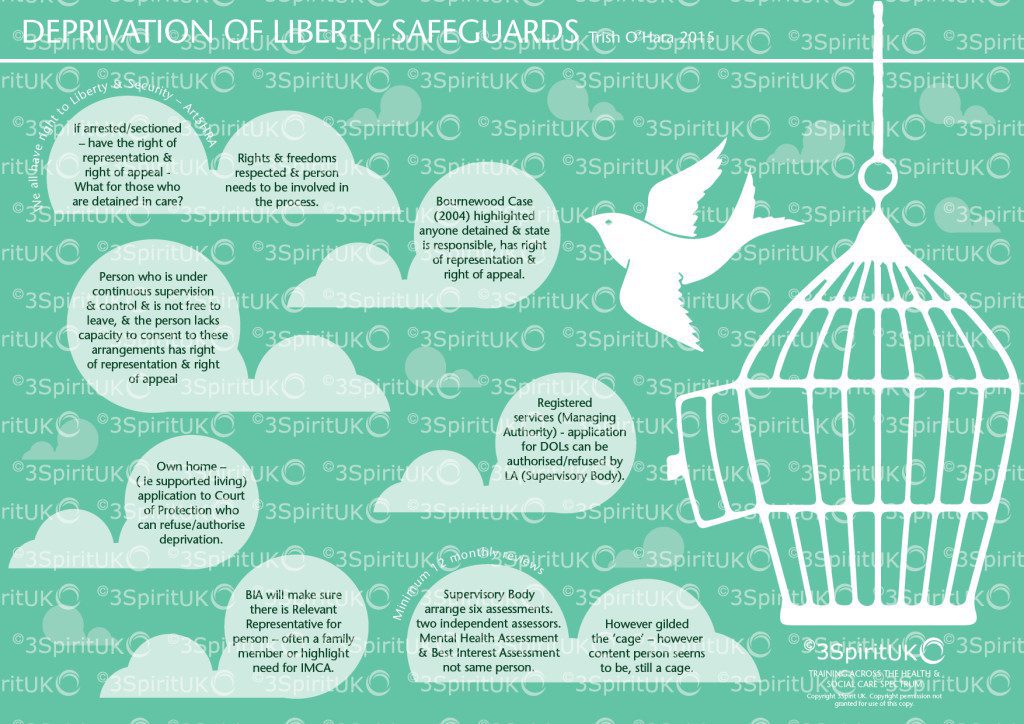

I for one, am fully aware of the necessity of adhering to Article 5 of the ECHR and delighted that Lady Hale pointed out that however golden the cage, it is still a cage.

But, the new threshold following the Cheshire West ruling :-

Continuous supervision and

Lacking capacity to consent to remaining

And how it falls within the Human Rights legislation:

The objective element: i.e. that the person is confined to a particular restricted place for a non-negligible period of time;

The subjective element, i.e. that the person does not consent (or cannot, because they do not have the capacity to do so) to that confinement;

State imputability: i.e. that the deprivation of liberty can be said to be one for which the State is responsible.

seems to have created an unprecedented amount of paperwork for those who, perhaps, need to be focused on emergency situations in hospital.

I am fully behind the new ruling for those living in residential care homes, nursing homes and hospices but am not sure this is money well spent on those in Intensive Care Units and in transportation from one hospital to another. It seems to me that those completing the assessments – such as Section 12 doctors and Best Interest Assessors are in the lucrative situation of charging £250 or so to assess people who are sick in hospital for a week or so. The nursing staff having to make applications, to spend time with the assessors – all of which is time away from using their expertise in keeping the person alive. I am aware that on many occasions, assessors have gone out to complete an assessment and the person has either gained capacity or indeed died or been discharged. I expect the assessors are still paid for their time and yet more public money is swallowed by this over-zealous interpretation of the ruling.

Of course, when a patient is resisting treatment and needing restraint, there needs to be protocols in place to ensure it is to maintain the life of the person, but can this not be regulated within ordinary hospital procedures?

Public monies are a dwindling resource as services face further cuts. Surely, there needs to be a common sense approach to deprivation and when it is necessary to authorise it.

I understand that new guidance is due to be published in 2017 which I hope recognises the paper driven exercise that often seems both pointless and expensive.

Yes, all patients should be informed and asked to sign consent for a time when they may not have capacity, following an operation and yes the MCA is a wonderful piece of law that protects the rights of all of us. But, the idea that a person who has suffered perhaps a head injury in a road accident and needs to take an ambulance for numerous hours to a specialist hospital needs a DOLs seems to me to be wasting peoples time and money.

I am not sure there is enough emphasis yet on getting this right where it needs more attention, time and money spent.

Are there enough home care providers who are involved in supporting a deprivation in a persons own home, not registered, trained in understanding liberty?

Do families understand that deprivation of liberty may be seen as false imprisonment?

Do enough care homes understand the right for people with capacity to make unwise decisions?

Do enough supported living services realise that they may need to apply to the court of protection if they are depriving a person of their liberty?

Surely, these are the areas of real concern. And where assessment and monitoring is most needed.

I await 2017 publication with much anticipation.

Trish

Follow UsShare Us